Pillars Fund

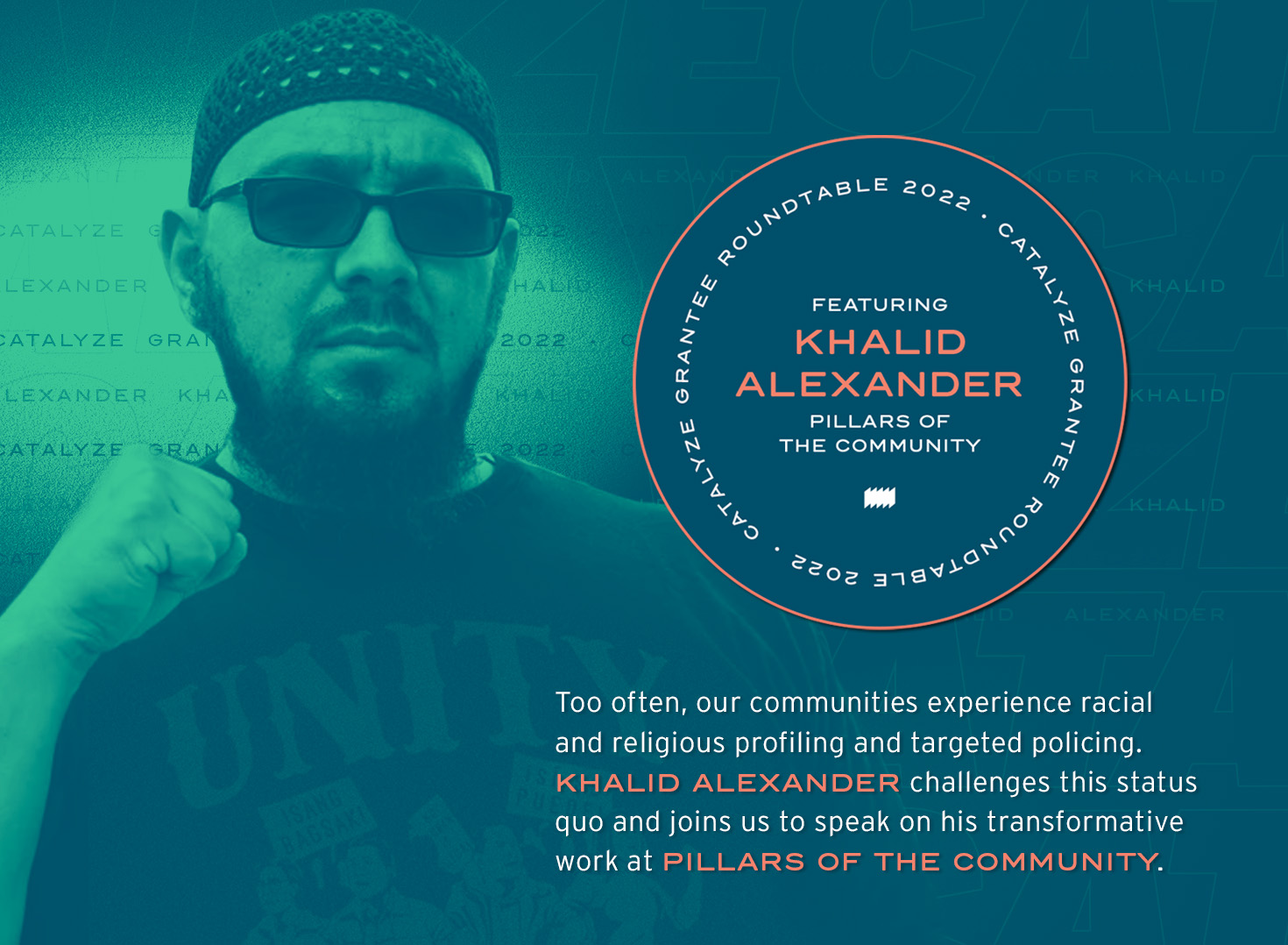

Conversations with Grantees: Meet Khalid Alexander

/ August 25, 2022

A proud resident of Southeast San Diego, Khalid Alexander is the founder and president of Pillars grantee-partner Pillars of the Community, where he works to challenge police harassment, gang documentation, racial profiling, felony voter disenfranchisement, and cruel and unusual punishment in sentencing. Pillars of the Community puts pressure on local San Diego elected officials, boards, and commissions to be accountable to the communities they serve and decrease unjust criminalization; they also teach those closest to the pain how to become community leaders and create sustainable change.

Khalid recently joined our roundtable of three Pillars grantee-partners to share his story. Khalid took us back to the moments that inspired his journey to nonprofit leadership, explained why incarceration is an essential issue for Muslims to address, and explored how Islam informs his work.

This is the second of three excerpts from our conversation with Pillars grantee-partners. What follows are responses from Khalid, edited for length and clarity.

The United States is the world’s leader in incarceration—there are nearly 2 million people in our nation’s prisons and jails. Why is it important, especially for Muslim communities, to address this criminalization?

If you study those things in the Quran and the hadith and pious people from the history of Islam, there’s consistently an emphasis on the poor and helping the poor. There’s a consistent emphasis on helping those people who are oppressed. I think what most people in this country don’t understand is that those are exactly the people that the criminal justice system is set towards punishing.

If you look and you ask your DA, or if you ask a police officer, how many people have you arrested this week for wage theft? The answer is gonna be zero. But if you ask how many people have you arrested for being vagrant in front of a business, the answer is going to go up. So I think the first key is to understand who’s incarcerated and why, and who avoids incarceration and how are they able to avoid it.

The second thing is once we actually see what happens after someone is incarcerated, I think there’s very little Islamic rulings that can support the incarceration system that we have today. I think it’s more haram than a double bacon cheeseburger that you rinse down with a bottle of beer.

Some of these cages, for example, in San Quentin: If any of us were to stand up, and we’re all different heights, and you were to spread your arm, you wouldn’t be able to completely spread your arms out. That’s how narrow these cells are. And those cells have two people in them, two bunks in them, a small desk, and a toilet, all in the same area. These are conditions where Americans would never be able to accept placing animals in.

The fact that we, as Muslims, aren’t aware of these [things], I think is extremely important, but I also think that we have the best tools to be able to address it. I really do view that the alternative worldview and the same thing that others us in the eyes and the light of other communities is exactly the thing that’s going to enable us to help lead other people to a more liberated and free world where people are actually treated as human beings.

How did you get involved in social justice-related work?

There were three major incidents that happened to get me more involved in social justice issues. One of them, I was teaching at the time, and I had a brilliant student, formerly incarcerated, who was always participating in class. Two weeks before finals, he ended up being incarcerated. A parole officer had visited his house and found a blue shirt on the ground of his closet. And because he was a documented gang member, used that to violate his parole and send him back to prison. As a result, he ended up dropping out of school.

Also at the same time, I had moved to an area of San Diego called Southeast San Diego. I was pulled over three times in a period of two weeks, and there were two questions that stood out to me that I was being asked. One of those is “Are you a fourth waiver?” Which is, many people who after release from prison are forced to sign away their fourth amendment rights. And so you can be stopped, hassled, searched. And the other question was “Are you a gang member?” At first, I thought that these questions were meant to figure out who I was and whether or not I posed a threat, but quickly found out that really these questions were being asked to find out how many of my rights they could get away with violating.

And then the third major thing that happened is about seven years before, I was a voluntary imam in one of the local jails. And a lot of the brothers were just getting home after six, seven, eight years of incarceration and were facing all of the obstacles to re-entry. Initially, we started off as a service provider thinking, hey, let’s just get people into jobs. Let’s help them with their resumes. Let’s help them find housing. But [we] quickly realized if you’re not addressing the cracks that led to incarceration in the first place, essentially the work that we are doing was like filling a bucket up that had holes at the bottom. No matter how much water you put into it, it’s impossible to fill it. So we quickly transitioned from being a service-oriented organization to an organization that really looked out for systemic issues and the policies that led to incarceration.

Nonprofit work can be challenging at times, especially when change is slow and progress is hard to see. Can you tell us about a win, a time when you felt encouraged and reassured by the power of your work?

My political growth and understanding of the work continues to expand on a daily basis. Around 2014, in the work we were doing around racial profiling, we were putting a CD together with local gang members who were also recognized for some of their rap skills. And we found out that one of the artists was incarcerated.

So rather than just give up on him, we were like, well, maybe we can give him a beat and give him something that he can rap over the phone. So when I went to visit him in jail and asked him why he was incarcerated, he said he didn’t know why. And that the lawyers didn’t seem to understand what he was being charged with either. Come to find out that then District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis had rounded up 33 African American men, some of whom weren’t even living in the state of California, and charged them with 50 years to life based off an obscure penal code 182.5, which passed in 2000. Under this penal code in court, she said that she can charge anybody who is part of an alleged gang that has allegedly committed a crime. Most of the defendants ended up taking plea deals; two of them, Aaron Harvey and Brandon Duncan, the rapper that I mentioned earlier, actually fought the case. Because we were able to get a number of the community members involved in this case, both Brandon and Aaron’s case ended up being thrown out.

From those efforts, we began doing a lot of work around what it means to be a gang member and whether or not people should be charged with it. We were able to do an audit of the California gang database. In that audit, I think they found something like 40 infants who were also documented as gang members. Until that time, people weren’t able to find out whether they were in the database until they were standing in front of a judge or being charged with a crime. We were able to pass a law that made it so that you can find out that and that you would be able to actually challenge whether you were on the gang database or not.

Although I’m proud of the policies that came about from the work, what I’m more proud about is we’re actually beginning to address this narrative around gang membership and whether or not somebody based off the way they dress, how they talk, or where they live should be incarcerated. And so in the process of pushing for this policy, we’ve actually been able to build a strong community power that’s able to address issues as they come up.

What role does spirituality play in your approach to your work?

All of the work that we do is very spiritual work for me. It’s difficult work. I don’t think i would be able to do it if I were not Muslim. I don’t think I would be able to do it if I didn’t have a deep understanding that Allah is the one who’s in control. That what we are going to be questioned about on the day of judgment isn’t What did you accomplish? but What did you try to do?

Every once in a while we have a win, but the results aren’t really in our control. The results are in the hands of Allah. So that’s the spirituality that gets me through all of the really frightening times that we’re living in and that people like African Americans and Native Americans have had to deal with from the time that Europeans came to the country or that Africans who were brought here as slaves and chattel.

At Pillars, we believe our communities deserve not simply equality but also the right to a joyful existence. In the spirit of that value, where do you find your joy?

Absolutely family, spending time with my kids, and coffee. Those are my obvious points of joy.

A huge part of what drives me is this realization that if we were to ask most people what have Muslims done for you, or how have Muslims helped your own lives, and the realization that most people probably wouldn’t be able to answer that in the affirmative is something that causes me as somebody who loves Islam and somebody whose life has been transformed by being Muslim and by being around other Muslims, it causes me a deep kind of pain knowing that most people haven’t been able to benefit in the same way that we have. And so in the same way, when I do see Muslims that are doing actually trying to make effort to make the communities they’re a part of better, to actually make oppression and pain and hurt less for other people, not necessarily because they’re Muslim but because they’re creations of Allah and that they’re a part of our larger family of Allah’s creation, that really does bring me a lot of joy.